About the Project: A Light Within (The Accessible Gospel of Thomas)

This work combines the arts, humanities, and interpretive sciences. I am developing a book/multimedia project understood in simple terms as an accessible, illustrated Gospel of Thomas.

The Gospel of Thomas is a still relatively little-known document, yet one of world-historical significance. Unearthed in the Egyptian desert in the 1940s and translated over several ensuing decades, it is now understood by scholars to be a key original source of the known sayings of Jesus of Nazareth – some previously unknown – a source rivaling and even exceeding some of the canonical (i.e., New Testament) gospels in authenticity. That’s an extraordinary discovery and assertion: that, after 1,800 years, one of the world’s dominant religions may be significantly reinterpreted in its light.

Thomas deserves to be understood better, but there’s a problem. It is merely an unordered collection of sayings, with no coherent narrative thread. Further, it is enigmatic and at times obscure and even seemingly paradoxical. While some individual sayings are surprising, and perhaps even suggestive of a “different” Jesus — particularly in his pointed messages concerning wealth and power — there is, unlike in the familiar biblical gospels, no clear story for the reader to follow and find their footing.

This project provides several innovative methods for making the text more accessible to readers and viewers.

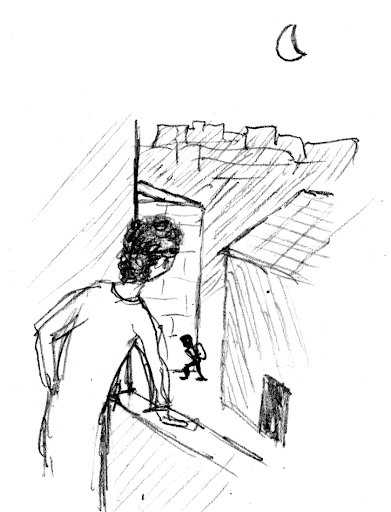

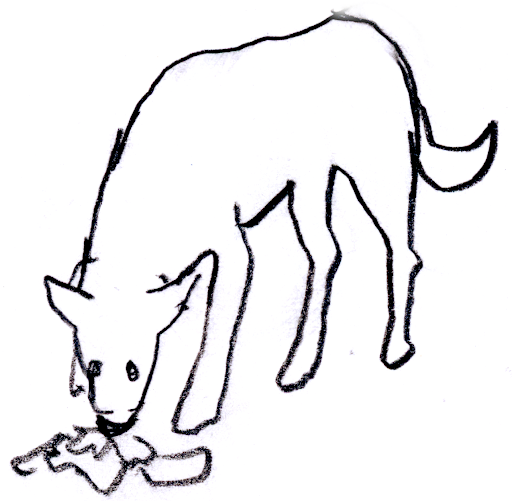

Illustrations: The language of Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas is visually evocative of a “simpler” time than our own. By showing fairly literal, of-its-time imagery that mirrors the written words and phrases, it becomes easier to enter into the world revealed in the text. Initially, I thought not to tell a story in the manner of a graphic novel, but rather compose a visual ‘cloud’ alongside a complete saying. But I have come to recognize that comic-standard panels deliver the text’s concepts more easily to the reader, so at present, the project presents a transitional combination of these approaches.

Reordering: I have re-ordered the 114 distinct sayings into 16 new thematic sections, so as to bind together key concepts and provide a comprehensible narrative flow.

Interpretive headings: Sections are titled and captioned, and sayings are given brief summary headings to ease the reader’s work of interpretation.

Format: As currently drafted, the images and text inhabit a book format with a wide page for each saying, containing summary heading, original saying, several images, and brief commentary. This format will likely evolve in its next stage to graphic novel-style panels to tie the text and images together more directly and strengthen the narrative flow. Ultimately, though, the preferred format is expected to be a contemplative video for web distribution, with audible text, static images proceeding in sync with the text, and perhaps accompanying music, coloration, and other effects.

Translation for contemporary understanding: While currently using the Scholars Version translation, some key words and phrases, such as “disciples” and “the Father’s imperial rule” (the Kingdom of God), are given new translations intended to open the text in a more immediately accessible way to the widest possible audience.

Commentary: I expect to add brief commentaries on the sayings to clarify obscure meanings, share scholarly judgments of authenticity, and, perhaps, occasionally suggest contemporary relevance.

About the artist, Nate Binzen: With this project, I am emerging as a visual artist. My professional track in recent years has been as a school administrator and teacher (of psychology and history; adult English Language Learners, high school seniors, and teenage OCD patients in treatment). My lifelong involvement in art was, until recent times, somewhat channeled into assisting in the work of my late father, a photographer and author of more than a dozen illustrated books, mostly for children.

Informed by my Masters in Theology, my consideration of the vivid visual evocativeness of certain ancient scriptures awoke in me a desire to build and harness my drawing and storytelling abilities to allow some of these texts to be considered in a way they have not been before. They were, after all, written for largely illiterate audiences, for whom various visual aids were provided down through the centuries. After reading such texts as a scholar, it dawned on me that they are susceptible of a new kind of treatment to enable our own visually-inclined generations to consider what meaning found within them might be of value. The Gospel of Thomas presented itself as particularly suitable for such an approach, for its enigmatic place in the scriptural firmament as much as for its gnomic language and suggestiveness to the mind’s eye.